An introductory history to The US War on Drugs, changes to the legislative and policing approach to drug possession in the 1980s and 1990s and hip hop music’s cultural response.

Introduction

Neoliberalism as a political project can be understood broadly as an effort to liberate capital from restraints imposed by the regulatory powers of the state, accompanied by a rolling back of social programs intended to provide a minimum standard of living, to instead allow for greater competitiveness and individualism within a more austere framework. In the social world of the United States, a key component of this ideological shift has been the reframing of a range of social problems, so that they are understood as failures of personal responsibility, rather than structural issues that can be addressed collectively, by deploying the resources of the state. The thrust of this change is well encapsulated in the Margaret Thatcher quote: “Economics are the method; the object is to change the soul”. 1

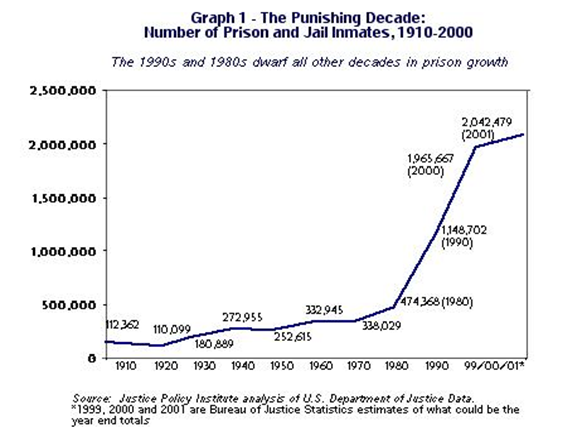

This long read explores the interconnectedness of neoliberalism to the War On Drugs, which has functionally been the primary means through which the prison population was radically expanded in the 1980s and 1990s, with a package of legislative measures which had the clear effect of targeting African American populations for lengthy carceral sentences for often minor drug offences. As a result of this, an enormous and profitable prison sector has emerged.

As a cultural medium, hip hop music is highly relevant to this history, as its emergence and ascent occurred alongside the deepening of neoliberalism and the war on drugs as phenomena in the two decades immediately before the end of the millennium. In the works of different artists it can by turns reflect the adoption of an at times archly neoliberal ideology, but also currents of conscious resistance, including anti-policing and anti-incarceration rhetoric, that go to the heart of the relevant structural crises.

In outlining this history, I also ask – if The War On Drugs and the resultant Prison Industrial Complex are failures by any measure other than the establishment of commercial partnerships between the state and corporations, the accumulation of profit, and the confinement of record numbers of ethnic minorities, what is the alternative? 2

2

The war on drugs

The War On Drugs is a term coined to denote a legislative policy change – originating within the presidency of Richard Nixon. Ostensibly, this term entails criminal justice policy efforts to deter drug dealing, and following from this, drug use. The most notable effect has been a radical expansion in the range of offences that carry prison sentences, and from this, a sharp climb in the prison population, beginning in the 1980s, and continuing through the 1990s. Of this greatly expanded incarcerated population, African Americans make up a hugely disproportionate share.

In order to appreciate the drastic nature of both the expansion in prison population, and the highly racialised character of this expansion, we might note that the United States incarcerates more than 2 million people, and that of this number, 450,000 are incarcerated for non-violent drug offences. This latter number is higher than the total incarcerated population for all offences across all European nations. In contextualising the racial component of this jump in incarcerated people, we might also note that African American men are around six times more likely than white men to be incarcerated, and that in accounting for inmates, African American men outnumber white men, despite African American people comprising just 12% of the total population. 3

The roots of the ideology which inaugurated The War On Drugs, as originally conceived, are themselves racist, and reflect the machinations of the Republican Party in the immediate aftermath of civil rights and growing opposition to the war in Vietnam. This was referenced by Nixon aide John Erlichman in a candid 1994 interview, in which he remembers the social forces identified as problematic by the American right at the end of the 1960s: “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the anti-war left and black people” 4

This brand of right wing politics with a clearly reactionary intent on questions of racialised policing, would also be robustly referenced by senior Republican Strategist Lee Atwater, following notable Republican electoral successes in the 70s and 80s:

Atwater explains that even references to ideas as seemingly innocuous as lower taxes, states rights and the like are understood as connoting punitive and retaliatory social consequences for African American communities, the effect of which is viscerally understood and welcomed by the most racist sections of the Republican party’s base of support.

Policies

In her work “Golden Gulag”, academic Ruth Wilson Gilmore regards the system that has delivered mass incarceration as one where punishment has come to be mass produced, much in the way cars are manufactured. One way this has been achieved is in the broadening out of the array of offences that carry a jail sentence, and the lengthening of these sentences.5

This process did not accelerate significantly until the presidency of Ronald Reagan. Reagan would eschew Nixon’s more lenient twin approach of treatment and some incarceration in favour of less of the former and much more of the latter. The work of Smith and Hattery in defining the growth of the Prison Industrial Complex in the neoliberal era shows that the explosion in incarceration can be attributed particularly to the following changes to criminal law:

– Recategorisation of small possession offences from misdemeanours to felonies, passed in the 1986 Drug Abuse Act.

-Longer sentences – as at 2006, the average sentence received by a crack cocaine defendant was 11 years.

-Mandatory minimums – following the passage of the 1994 Crime Bill, a crack cocaine possession charge of just 5 grams carries a minimum term of 5 years. This policy would stand for 16 years, before being repealed by President Obama.

-“Three Strikes, You’re Out!” – A Clinton era law which imposes a mandatory life sentence for a third felony conviction. 6

Perhaps the most striking difference in treatment in these provisions is in the different quantities required for a five year sentence. For the same carceral term to be mandated for cocaine possession, it would take 500 grams – a 100 to 1 disparity. This is significant, as cocaine was regarded as a drug of the American middle class, and was thus given a patently more lenient treatment than crack – the drug most synonymous with African American inner cities, and something of a moral panic within the American political establishment.

Why America under neoliberalism needs a Prison Industrial Complex

In understanding why the prison population has increased so vastly, and why this is desirable for the neoliberal state, it’s should be understood that there are sections of the population who are viewed as not only insufficiently economically productive, but who also lack the resources and disposition to become productive, and are thus better off confined in prison. For sociologist Eric Olin Wright, this is the underclass – which disproportionately includes African Americans:

“In the case of labor power, a person can cease to have economic value in capitalism if it cannot be deployed productively. This is the essential condition of people in the ‘underclass.’ They are oppressed because they are denied access to various kinds of productive resources, above all the necessary means to acquire the skills needed to make their labor power salable. As a result they are not consistently exploited. Understood this way, the underclass consists of human beings who are largely expendable from the point of view of the logic of capitalism. Capitalism does not need the labor power of unemployed inner city youth. The material interests of the wealthy and privileged segments of American society would be better served if these people simply disappeared.” 7

Angela Davis posits prisons’ expanded role as inevitable in this historical era – due to the globalisation of production, and the resultant deindustrialisation of global north countries like the US, entire communities – once employed in manufacturing – now lack the means to viably reproduce themselves and sustain functioning familial and community bonds, and thus cease to be useful for the continued economic functioning of the state. 8

We should also note in considering deindustrialisation and the corresponding explosion in prison population that a precedent exists here. The reconstruction era of the United States would see the state’s attentions in the southern Unites States turn to law changes that would lead to the rapid criminalization and incarceration of former slaves, who would typically then be put to work by the penal system on tasks similar to those that once would’ve previously been performed by enslaved people.9 This parallel highlights what Stuart Hall and Bill Schwarz would regard as a crisis of social reproduction: “Crises occur when the social formation can no longer be reproduced on the basis of the pre-existing system of social relations”. 10 Simply put, in both instances, the state has responded to crisis by opting to incarcerate people, and has achieved this by criminalising a greater range of social practices.

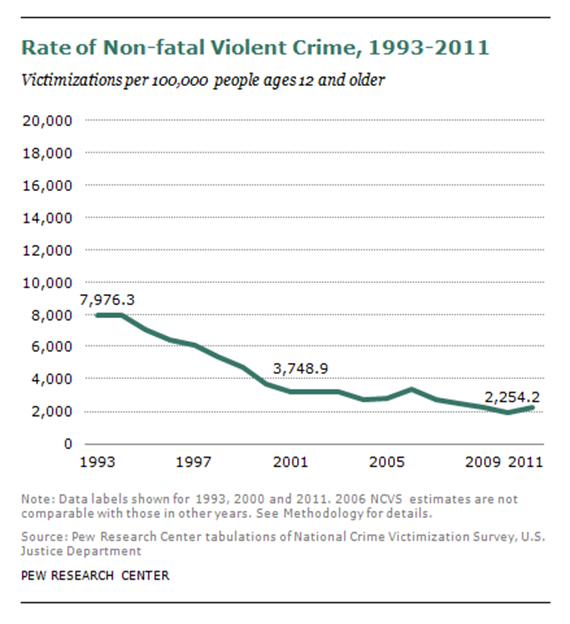

This process becomes culturally normalised for the general population, courtesy of the presence of news media platforms – beginning in the 1980s, 24 news channels would begin to provide a non-stop focus on crime, fostering the perception that inner city, predominantly black communities were becoming out of control. This news environment has continued to maintain this influencing role up to the time of writing, even though violent crime in the US has been in decline since the early 1990s.

11

Aggressive policing

While the legislative changes on drug possession are important in explaining the rise in the Prison Industrial Complex, so too are changes to policing. The presidency of Bill Clinton would see a significant expansion in the scope of policing, as well as the resources allocated to it. Clinton’s government would expand the Drug Enforcement Administration. In this period, the police would be granted new powers to enter homes without a warrant. 12 SWAT team use to enter homes would increase significantly, and the controversial practice of stop and frisk would come to be used significantly more, disproportionately targeting young African American men. As sociologist Alex Vitale also troublingly notes, policing has increasingly intervened to deadly effect as mental health services have atrophied – officers are armed and trained to neutralise perceived threats with force, and are not trained to understand the behaviours of individuals suffering with the effects of a mental health crisis, which they often misinterpret as threatening behaviour. 13

A by-product of the over-policing of African American communities has been the regular incidence of police brutality, often resulting in deaths of suspects and innocent parties in the vicinity. Eric Garner died shortly after being restrained during an arrest in 2014 – he was suspected of selling loose cigarettes on the street. 14 In 2020 Breonna Taylor was shot dead by plain clothes police who had forcibly entered her boyfriend’s apartment executing a search warrant for drugs, which were not found. She was unarmed and in bed. 15

Poverty and household debt also play roles in increasing the risk of incarceration. The work of Le Baron and Roberts in “Confining Social Insecurity” demonstrates that increasingly consumer borrowing is financing basic living costs as a result of flatlining wages, at a time when incarceration for debt owed has been revived as a practice. Meanwhile, healthcare is not a right, and is not affordable for tens of millions of Americans, a disproportionate number of whom are African American. Perhaps most significantly, activities associated with those living in poverty – including panhandling, “loitering” and sleeping in public places have become criminal offences under neoliberalism. 16

The combination of legislation designed to target African American populations, aggressive policing, the loss of decent employment opportunities, institutional prejudice, and increased poverty cluster together as factors which negatively impact social reproduction, consolidate inequalities, and sustain the likelihood that African Americans will continue to be incarcerated at higher levels.

Incarceration

Incarceration in the United States under neoliberalism is characterised by the absence of any commitment to rehabilitation. Criminal justice and society itself is informed by what sociologist David Garland calls a “criminological structure of feeling”, in drawing on the ideas of Raymond Williams. 17 Under this social condition, criminal justice as defined by law, becomes a stand in for a more meaningful social justice. For Garland the key measure of this is simply that the US incarcerates more than any society in the world, and the incarcerated population is disproportionately drawn from the poorest and most marginalised in society. 18 Criminal justice thus takes on a retaliatory and exploitative character.

As Wilson Gilmore argues, mass incarceration in the United States does little other than house disadvantaged people away from their families and communities for long periods of time, contributing to family breakdown, and the material and cultural impoverishment of communities. 19 Prison does not teach the inmates skills that will be beneficial in the workplace, but instead exploits their Labour at a rate well below the minimum wage. 20

Angela Davis observes that it will be difficult to reduce the size of the carceral system due to the complex network of partnerships between the state and privately owned prisons, companies that employ prisoners as well as corporations who sell exploitative and expensive services to prisoners – such as overpriced telecoms services. Because this complex of mutually sustaining partnerships is in place, the private entities that form part of this complex are financially incentivised to lobby government not to move in the direction of greater lenience or decriminalisation of presently carceral offences. Simply, the prisons exist, and they must be filled, or else profit declines. On the question of rolling back the influence of private enterprise over policy, instances of brutal behaviour and misconduct against privately operated prisons have frequently not led to the withdrawal of contracts in instances where such events have come to light. 21

Resistance

The threat of prison for minor drug offences as a reality in the social world is something well understood within African American culture, and hip hop music especially reflects a knowledge of the racism of drug laws, the aggressive policing of racial minorities, and the way these forces work to cement inequalities.

Many hip hop songs about incarceration are delivered with defiance, especially towards police and prison guards, and by extension the racist social order for which they are agents. Public Enemy directly address the issue of crack in their track “Night of the Living Baseheads”. While the lyrics of the song admonish African Americans who sell drugs, the track opens on a sound clip from prominent former Black Panther Khalid Muhammad, addressing the radically dispossessed nature of African Americans as being a key precondition for crack use:

“Have you forgotten that once we were brought here, we were robbed of our name, robbed of our language. We lost our religion, our culture, our God … and many of us, by the way we act, we even lost our minds.”

This sound clip contextualises drug use and social breakdown within the long history of black dispossession and confinement, dating back to the earliest history of African American slave voyages, continuing through the long history of slavery, through the Jim Crow era, and entering the neoliberal era of skyrocketing incarceration due to drug use. The choice of Khalid Muhammad is also significant, as due to his history as a member of the black panther party, he represents the revolutionary political ideology that would be identified as a threat by conservatives decades earlier in the Nixon era.

Another rap artist who addressed themes of aggressive policing, stop and frisk and the attendant danger of incarceration for minor offences, as well as the key role of incarceration in long term damage to communities is Tupac Shakur, and much of this is neatly captured in the 1991 track Trapped: “Too many brothers daily headed for the big pen’, Niggas comin’ out worse-off than when they went in.”

“They got me trapped, can barely walk the city streets. without a cop harassin’ me, searching me, then askin’ my identity. Hands up, throw me up against the wall, didn’t do a thing at all”.

Tupac – alongside incarceration – addresses the very real danger of being killed by the police, as well as complicated issues to do with his ability to empathise with police as humans, whilst recognising the structural violence and racism of which they are the agents: “Coppers try to kill me, but they didn’t know this was the wrong street. Bang bang, count another casualty. But it’s a cop who’s shot for his brutality. Who do you blame? It’s a shame because the man’s slain. He got caught in the chains of his own game. How can I feel guilty after all the things they did to me?”

Demonstrating the persistence of the connectedness of drug laws and incarceration for African Americans well beyond the 90s, more contemporary rappers have also drawn on these themes in their work. At the 2025 super bowl half-time show, Kendrick Lamar’s set was designed to suggest that his dancers were performing a routine inside a prison yard. Lamar also incorporated carceral imagery at the 2016 Grammys, when his musicians would perform inside prison cells on the stage.

Lamar’s lyrics reference the drug use in communities such as the Compton neighbourhood of Los Angeles where he grew up: “I live inside the belly of the rough, Compton, USA / Made me an Angel on Angel Dust, what?”

Although never himself incarcerated, like many African Americans who end up in prisons, Lamar would witness a murder at a young age, as a teenage drug dealer was gunned down in front of his apartment building. This was not the only murder he would witness as a child. 22 Given Lamar’s formative experiences, it’s unsurprising that he uses lyrics and imagery to explore drug use, incarceration and systemic racism with his mass audience.

Hip Hop music also at times embodies the aggressive acquisitiveness of the neoliberal social order, and it’s quite normal for artists to use their lyrical content and music videos to brag about their self-made wealth, and play up affectations of entrepreneurship. Rapper and record label boss Jay-Z’s record label Roc-a-fella Records is a play on words named closely after the eponymous Rockefeller family of industrialists, synonymous in American culture with oligarchic power. Jay-Z is business-minded, and relishes any opportunity to build his empire of music, merchandise and influence.

The unified thread in much of the artistic production within hip hop is the centrality of violence – violence is often in close proximity to every day life for African Americans, as Angela Davis points out –

A recent development in the history of resistance against policing and incarceration is the Black Lives Matter movement. I have chosen not to centre this here, as it’s a more recent phenomenon to have arisen within later neoliberalism. There is also so much to say that it might pull away focus from the relationship between drug legislation, policing of African American communities, and the initial development of today’s Prison Industrial Complex, as well as how this was reflected immediately in the culture. It seems clear that awareness of this deleterious combination of social forces explains much as to why BLM exists; its core mission is plainly a call for overdue justice, that the state has failed to deliver. Tellingly, key events in the history of BLM as a movement have been catalysed by instances of police brutality in response to suspected minor offences, generating a visceral reaction in African American communities and well beyond. 23

Alternatives – decriminalisation & abolition

Criminalisation and the move to tougher sentencing since the 1980s has not been successful on its own terms – despite the significantly tougher sentencing and policing, Pew Charitable Trusts research found that overall consumption of drugs and rates of recidivism in the 1980s and 1990s did not decline. The recasting of drug use as an issue of failed personal impulse management, now decades old has not borne fruit. 24 In the case of crack, rates of use were already declining before the introduction of the 1994 crime bill, further building the case that the use of particular drugs may climb and fall due to a number of factors in the social environment, and that carceral deterrents are not influential by themselves. The muscular approach to drug crime has only succeeded in filling newly constructed prisons with record numbers of African Americans, made policing more deadly for this same community, and granted the state the power to surveil those suspected of often minor offences for years at a time. Historians like Elizabeth Hinton also persuasively argue that the swelling of criminalisation by the government has been an inevitable response to the gutting of anti-poverty spending originally introduced by Lyndon Johnson – problems that might be addressed in the community instead become the remit of policing and criminal justice, whose logic is only ever to discipline and confine people away from society. 25

The approach of Portugal to drug use surely suggests a viable alternative that the US could emulate – drug related deaths have declined substantially since the 2001 rollout of a package of decriminalisation measures for small quantity drug possession. HIV transmission which was historically related to high heroin use in Portugal has also receded from over 500 new cases per year in the early 2000s to just 13 cases in 2019. Drug users are assessed to ascertain whether their drug use is a risk to themselves or others, and may be either referred to treatment or released with no further action, contingent on the level of seriousness. Under the Portuguese approach that embraces treatment rather than incarceration, figures suggest that the overall social costs related to drug abuse have declined by nearly 20% between 2001 and 2015. The success of Portugal has led to the rollout of limited decriminalisation measures elsewhere – notably in Oregon and Norway. These encouraging metrics should surely lend confidence to claims that a different future for US drug policy can be possible. The key question may be whether the US state has the will to dismantle the legislative framework and network of business relationships that work together to surveil, incarcerate and exploit. 26

- Skidelsky,R, “Margaret Thatcher – a strong leader, but a resolute failure by any other measure”, Guardian Online, 18 April 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/business/economics-blog/2013/apr/18/margaret-thatcher-leader-failure-strong ↩︎

- Hattery, A & Smith, E, “The Prison Industrial Complex”, Sociation Today volume 4 no. 2: http://www.ncsociology.org/sociationtoday/v42/prison.htm ↩︎

- Hattery, A & Smith, E, “The Prison Industrial Complex” ↩︎

- Lopez, G. “Was Nixon’s war on drugs a racially motivated crusade? It’s a bit more complicated.”, Vox, March 29, 2016: https://www.vox.com/2016/3/29/11325750/nixon-war-on-drugs ↩︎

- Wilson Gilmore, R, Golden Gulag, (University of California Press, 2007), 2-3 ↩︎

- Hattery, A & Smith, E. “The Prison Industrial Complex” ↩︎

- Hattery, A & Smith, E. “The Prison Industrial Complex”

↩︎ - Davis, A, Are prisons obsolete? (New York : Seven Stories Press, 2003), 66 ↩︎

- Davis, Are prisons obsolete? 67-68 ↩︎

- Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag, 54 ↩︎

- Drake, B, “Rate of non-fatal violent crime falls since the 1990s”, Pew Research Centre, June 14, 2013: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2013/06/14/rate-of-non-fatal-violent-crime-falls-since-the-1990s/ ↩︎

- Vitale, A, The End of Policing, (London : Verso, updated edition, 2021), 134-135 ↩︎

- Vitale, The End of Policing, 1 ↩︎

- “Eric Garner: NY officer in ‘I can’t breathe’ death fired”, BBC News, accessed 28 February 2025: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-49399302 ↩︎

- “Breonna Taylor: What happened on the night of her death?”, BBC News, accessed 28 February 2025: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-54210448 ↩︎

- Le Baron, G & Roberts, A, “Confining Social Insecurity: Neoliberalism and the Rise of the 21 st Century Debtors’ Prison”, Politics & Gender volume 8 no.1 (2012) ↩︎

- Bogazianos, D, 5 grams : crack cocaine, rap music, and the War on Drugs. (New York University Press: New York, 2012) 7. ↩︎

- Bogazianos, 5 grams, 8 ↩︎

- Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag, 14-15 ↩︎

- Hattery, A & Smith, E. “The Prison Industrial Complex” ↩︎

- Davis, Are prisons obsolete? 68-70 ↩︎

- Moore, M, “Kendrick Lamar’s Poetic Awakening”, The Nation, 8 October 2020: https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/kendrick-lamar-butterfly-effect-book-excerpt/ ↩︎

- McCracker Jarrar, A & Roth, K, “Justice for George Floyd: A Year of Global Activism for Black Lives and Against Police Violence”, Amnesty International, 24 May 2021: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2021/05/justice-for-george-floyd-a-year-of-global-activism-for-black-lives-and-against-police-violence/ ↩︎

- Vitale, The End of Policing, 145 ↩︎

- Geary, “From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America by Hinton Elizabeth”, The American Historical Review Vol. 122, no. 3 (June 2017): https://academic.oup.com/ahr/issue/122/3 ↩︎

- “Drug decriminalisation in Portugal: setting the record straight”, Transform Drug Policy Foundation, accessed March 1 2025: https://transformdrugs.org/blog/drug-decriminalisation-in-portugal-setting-the-record-straight ↩︎